On Code Structure

Code structure can be an important factor of a clean, well-organized codebase that is less intimidating to a new maintainer, and pleasant to work with for everyone. When done right, it can even beat a thousand word doc.

In my experience, the significance of code structure is either overlooked or over-engineered from the beginning. Both would supercharge the build-up of technical debts and sometimes could lead to a dead project sooner than you can say “refactor”.

By following a couple of simple conventions, we can make any project, almost language agnostically, better structured.

Make the filesystem work for you

First, make the filesystem work for you, not the other way around. You want the readers of the code to think as less as possible on how and where to locate the relevant code they’re looking for. Modern tools such as IntelliSense make this relative unessential, but we cannot assume everyone has them available all the time.

This is more important if you work with a less opinionated stack or framework. In such a case, keeping a sane structure of files and folders would minimize frictions between maintainers, and across its development lifecycles.

There is no fixed “best way” to structure files and folders. But it’s important to pick one and stick to it.

For example, A Python API server project written in Flask may have a structure as below:

1 | ./src/ # project root |

In this example, comments are among the modules that are at the same level as users and posts. But by itself, it’s a file, while the other two are folders. I’ll explain more about this in the next point.

Progressive Refactoring

When you start on a new project or a new feature of a given project, it’s not a bad idea at all to put everything in one file. All until its size grows to a point that makes it hard to navigate through, then we start to divide.

This time we’ll take an Express.js based single-file router as a starting point, and gradually refactor it to a more manageable form.

We’ll start with

1 | ./src/ # project root |

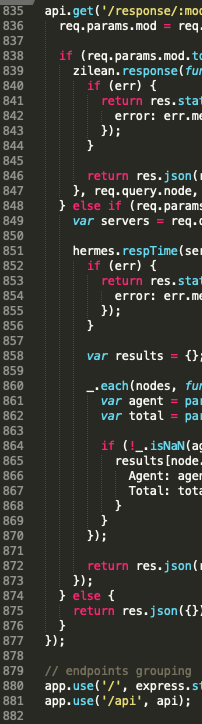

We’ll assume the content of app.js to be something like https://github.com/EQWorks/ws-product-nodejs/blob/master/index.js. It’s a nice little web server that serves some PostgreSQL driven queries, everything in one file with no more than 100 lines of code. Short, sweet, and everything within (one file) short reach.

But soon the project would grow into something like:

Navigating through this would be a nightmare and you can hear your inner self screaming “refactor! refactor now!”. So let’s refactor this, progressively.

$ mkdir app && mv app.js app/index.js

1 | ./src/ # project root |

The first action is to stop the bleed by turning the app.js file into a package form. This does not make the existing code any more pleasant than before, but any new changes will have more leg room to expand on while keeping usage of the entire module the same:

1 | // the usage of 'app' stays the same as before |

Then you can wield your refactor ax whenever and wherever you can, all in a naturally scoped package form app/ that wraps all the implementation details and groupings without breaking the API. At some point, the structure could look like:

1 | ./src/ # project root |

The evolution of the packages, sub-packages, sub-sub-packages, etc., all leverages the language’s filesystem-based package resolution mechanism (in this case Node.js, but similar with many), thus keeping the structure intuitive no matter how deep the structure tree goes, as long as the basic understanding of such mechanism is shared in common.

From within the code perspective, there are many strategies to divide and group. I like to keep as many things as pure functions as possible and keep them in an util.js module, or util/ (sub-)package. They can also be ./src/feature/util which is “local” to the given feature; or when a portion’s usage becomes common enough, refactored out to be a part of the “global” ./src/util. But that’s just one strategy among many. More discussions around this topic in the next point.

Grouping Conventions

No matter how much we leverage the filesystem based package resolution mechanism, there would always come the inevitable human-opinion based disputes. Developer A likes to call data interactions queries, while developer B prefers interfaces. Pick any, and stick through.

It is paramount though, not to confuse the readers of the code with misleading grouping. For instance, coming as a deeply experienced Ruby on Rails developer, it’s in their nature to group things by models, views, and controllers. But to adopt such grouping, in a more Sinatra-like stack (like Python Flask and Express.js from above), it is more important to communicate with the rest of the maintainers what belongs to where, so a view related functionality does not appear in the controllers group.

Or, simply follow a more natural convention. In the context of a web application, group by intended URLs the route handlers listen to would be an excellent way.

For instance, you would have two versions of the APIs, and a few API endpoint groups (the RESTful APIs term is “resources”):

1 | GET /v1/users |

Why not map that naturally to your files structure?

1 | ./src/ # project root |

This way, when a non-technical person complains that “users dashboard have X glitch in v1”, the developer can just go into ./src/v1/users, and have a much smaller scope to deal with, without spending much valuable brain-cycle on pinning where things are.

Final Remarks

All of the above conventions are quite loose and are intentionally kept so. This is because every stack has its own set of ground rules to follow and best practices to base on. Also, it is meant to be adapted with personal preferences to not overshadow but to signify your, or your team’s style. Furthermore, in this highly evolving world of software, to keep these conventions loosely and naturally applied would allow for the projects to evolve along.

Hopefully, by adopting some or all of the above conventions, and by adapting them with your personal preferences, you get to enjoy programming even more.